Slings and Arrows - A Retrospective

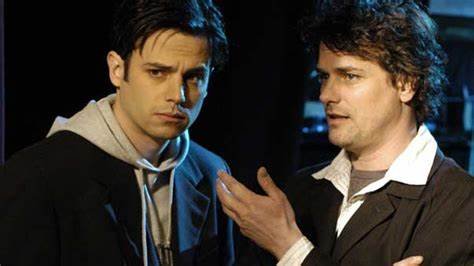

There are shows I come back to countless times. The West Wing, Blackadder Goes Forth, etc. Watching them is like visiting an old friend. They stay the same, but my connection with them evolves throughout the years. Slings and Arrows is one of those shows. It’s a brilliant comedy/drama series. David Simon, the creator of The Wire, said the show is “So clever it left me with pure distilled writer envy.” I cannot remember how I discovered it. I have been fascinated by the theater world since I was a kid. I have not gotten directly involved in theater, but I’ve been around it growing up. That is the main reason the show appealed to me. It is the story of the fictional New Burbage Theater Festival in Canada and those who work there, focusing on actor/director Geoffrey Tennant, played brilliantly by Paul Gross.

Geoffrey suffered a nervous breakdown for reasons I will not spoil, during a performance of Hamlet. After that, he fled the stage and refused to go back to the festival. Years later, he is forced to return when the aging artistic director, Oliver Welles, suddenly dies. I have to mention that minor spoiler: it is an important plot point since it happens in the first episode and sets up the rest of the series. Geoffrey threw away a burgeoning stage career and a relationship with his frequent co-star Ellen Fanshaw. Martha Burns plays Ellen with great neurotic energy. She drives the cast and crew at the festival bonkers, but beneath that surface-level maladjustment, she is a resolute and caring person.

After Oliver’s death, Geoffrey returns to the hallowed grounds that ruined his life. He takes over as interim artistic director, much to the distaste of many who still believe he is mentally unstable. He does not ingratiate himself with the cast when he openly insults Oliver Welles at his memorial at the theater. He believes Welles threw away his integrity and ruined the theater. A contentious viewpoint amongst the man’s loyal flock. Matters do not improve for Geoffrey when he starts seeing and communicating with Oliver’s ghost. Stephen Ouimette plays the late Welles magnificently. He was a defeated man who had shifted into autopilot and had very little passion left for his work before he died.

His return as a spirit prompts him to reevaluate the life he led and what he can do to atone for his mistakes. The back and forth between him and Geoffrey is the heart of the show. They have a lot of baggage in the past that weighs down their early interactions with venom and resentment. They soon learn to trust and understand each other. Geoffrey ends up relying on Oliver to guide him through the plays. Despite their issues, they need each other to move forward. Geoffrey cannot evolve until he comes to terms with his past and learns to address why Wells was an important part of his life. Oliver meanwhile feels like he must discover a higher purpose to move on in the afterlife. They both leaned on each other throughout the years and brought out the best and worst in each other.

Multiple character threads encompass the show’s central dynamics. Even the supporting players are given substantial development. One of the most tragic figures is Richard, the New Burbage festival manager played with brilliant perpetual anxiety by one of the show’s co-creators Mark McKinney. He desperately wants to be loved by those at the theater. They will forever see him as the talentless money man, which he pretty much is. Richard does not have a creative bone in his body, but his urge to be adored by those who do leads him down a path that molds him into whichever shape he believes will get their respect.

Rather than being a bland corporate stooge, Richard is a genuine albeit misguided person. He is dedicated to the theater and loves musicals. He constantly goes out of his way to help and support Geoffrey, even when plans are being hatched behind his back. This tension with the business and corporate end of the theater world is an insight into the disconnect artists often have with the money-making side of the operation. Geoffrey becomes more and more detached as his success grows. He yearns to return to the root of the text and what makes these plays so great, rather than be distracted by spectacle and crowd-pleasing.

There are a few Canadian rising stars throughout the show. Rachel McAdams plays Kate in season 1, a bright-eyed blossoming talent who develops a relationship with the Hollywood heartthrob playing Hamlet, Jack Crew, played with an insecurity-laden swagger by Luke Kirby. Sarah Polley is Sophie in season 3, an initially icy actress playing Cordelia in King Lear who ends up revealing herself to be a warm-hearted person with a wounded heart. All three actors would go on to have prosperous careers. There are far too many characters to adequately delve into here.

The show has a clever structure where each season is dedicated to the production of a Shakespeare play. Season 1 is Hamlet, season 2 is Macbeth, and season 3 is King Lear. There are branching narrative paths that support the main story. These backing elements are not the focus, but they lay the foundations for this world. We are immersed in the theater world and everything that entails. To those outside the theater scene, they may just seem like minor observations, but they are the building blocks of what makes theater such a unique and enthralling place.

These lifestyle snapshots could only have been written by those with in-depth knowledge of theater life. Anything from the theater bar the cast and crew frequent, the permanently frazzled stage manager Maria, played by Catherine Fitch, to the loyal and kind festival administrator Anna, played by another co-creator of the show Susan Coyne, who is the real backbone of this turbulent ensemble of misfits. One of the recurring characters, Darren Nichols, is one of my favorites. He is played with magnetic panache by Don McKellar. He is used sparingly, mostly because too much of him would be insufferable. Anyone who has worked in the theater long enough has met a Darren. He is a pompous hack director whose productions are an exercise in vulgarity. He strikes a perfect balance between infuriating and endearing.

Theater has gone through numerous changes since Slings and Arrows premiered in 2003. Season 3 introduces the divide between musical theater actors and the more serious Shakespeare performers. This still exists today to an extent, but there is far more crossover today. Actors often jump from musicals to dramas without missing a beat. Jesse Buckley for example went from playing Anne in the West End revival of Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music to brilliant dramatic roles in films like Wild Rose and I’m Thinking Of Ending Things. Slings can certainly approach farcical exaggeration territory with the way it portrays the musical theater actors. Never to the point of being insulting. Plus, having met many involved in this field I can fairly say their portrayal is often not far from the truth.

Part of what makes Slings and Arrows so special is the overall theme of being connected to something bigger than yourself. Being a part of a community all working towards a grand achievement. That feeling of unity binds them together. From an outsider’s perspective adapting Shakespeare may seem inconsequential in the grand scheme. It has been done countless times, so why do so many people do it? I touched on this briefly in my review of Joel Coen’s version of Macbeth. What makes Shakespeare’s work so great is how it is infinitely transformable.

Shakespeare’s words have an intoxicating grip on those who speak them. They get under your skin and compel you to perform. Everyone has a different method of playing the roles. Some get stuck in the old ways of playing the characters, like the blustering buffoon Henry Breedlove in season 2, played by the delightful Geralt Wyn Davies. He has played Macbeth so many times to the point where he has decided the only way to do it is his way. In season 3, the aging Charles Kingman, played by the great William Hutt, wants to play Lear one last time. He is a jaded and bitter person who constantly clashes with the cast. Lear means more to him than anything else. His dedication to the text is to the detriment of his camaraderie with his co-stars, but that concern carries little weight to him. The play is in his blood, scratching at his skin to get out in his final years.

These plays are a universal canvas for any artist to paint on. They can be sculpted into any form no matter who you are. For a brief moment in time, there is transcendental magic on that stage. Your voice intertwines with the text and shines through. There is no other storyteller in any medium whose work has that kind of ubiquitous power. Slings captures those elevated emotions better than any other depiction of the theater world. That is why I wanted to write about this magnificent show. The creators Susan Coyne, Mark McKinney, and Bob Martin have assembled a truly incandescent series.